Colour blindness, also called achromatic vision, is a condition that affects a person’s ability to recognize certain colors. The characteristic is usually inherited, meaning it’s passed to a person from a member of their family, and it affects males more often than females.

It’s also possible for achromatic vision to be acquired, which means it develops later in life.

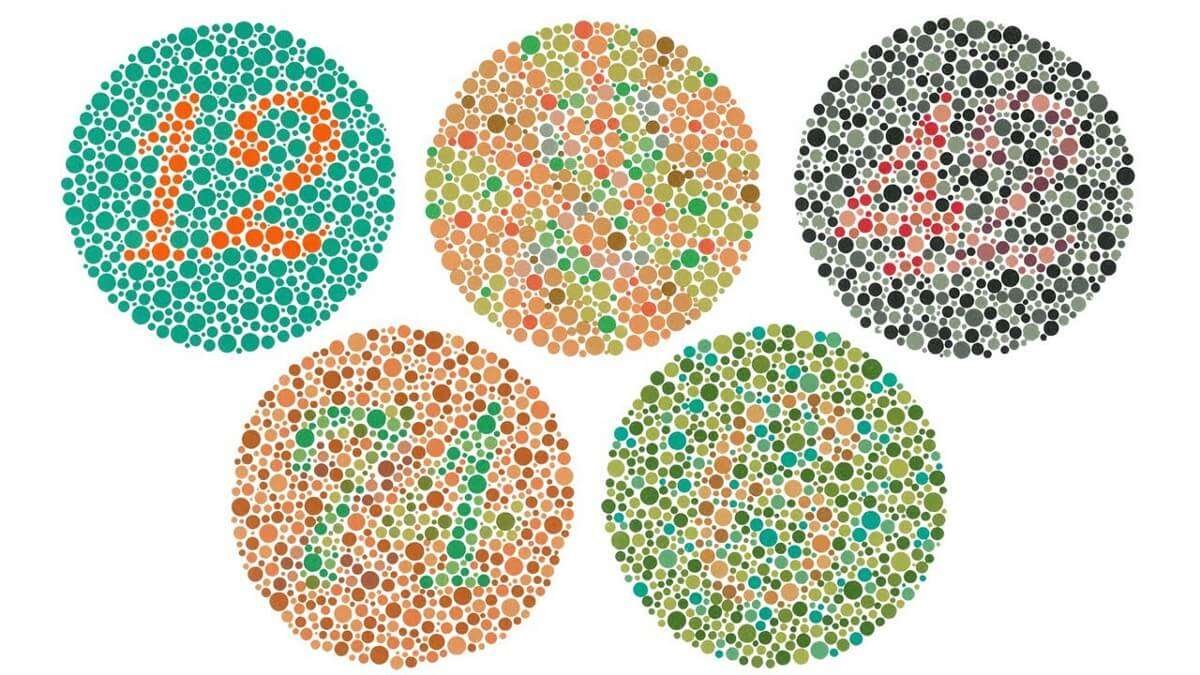

Like with many things, color perception is on a spectrum. There are different kinds of color blindness, as well as levels of severity. Below, we discuss the different types of color blindness, what causes them, and ways to improve achromatic vision temporarily.

Types of Color Blindness

Different color deficiency types are categorized by which colors are affected. There is often the misconception that achromatic vision literally means you see the world in shades of gray. While that is the case with complete color blindness, it’s very rare. Usually, being color blind means you have trouble differentiating between specific colours.

The most common type of color blindness affects red-green perception. Within red-green color blindness, there are four subtypes:

- Protanomaly – Impaired ability to see red, which makes red objects appear a dull greenish-gray. Colors that contain red (purple, orange, etc.) also appear dull.

- Protanopia – The complete inability to see red light, which means most objects appear in varying shades of gold or blue. Reds and greens cannot be distinguished.

- Deuteranomaly – The most common type of red-green color deficiency, it impairs a person’s ability to see green. Green objects may have a reddish hue and colors containing green appear dull.

- Deuteranopia – The complete inability to perceive green light. Reds and greens are not distinguishable and most objects appear in blue and gold shades.

A less common type of achromatic vision is blue-yellow color blindness, which affects a person’s ability to see shades of blue or yellow. There are two subtypes of this category:

- Tritanomaly – Affects the ability to see blue, which makes it difficult to tell the difference between blue and green. The colors red and yellow are also hard to decipher.

- Tritanopia – The complete inability to see blue. Tritanopia color blindness makes it hard to distinguish between blue and green, yellow and pink, and purple and red.

Two other types of achromatic vision are monochromacy (also called achromatopsia) and blue cone monochromacy.

Achromatopsia describes complete color blindness, in which all the color-sensing cells in the eye are either missing or impaired. People with this type only see in varying shades of gray. Other vision problems are usually present when a person has monochromacy.

Blue cone monochromacy is the rarest kind of color vision deficiency. With blue cone monochromacy, only one of the three types of color-sensing cells works. So, while someone with this type can sense blue light, they mostly see things in shades of gray.

Causes of Color Blindness

Your ability to see color comes from photoreceptor cells at the back of your eyes. Photoreceptors consist of rods, which are highly sensitive to light and help you with night vision, and cones, which give you the ability to see the color spectrum.

Cones take the light that enters the eye and translate it into various colors. There are three different types of cone cells that are categorized as S-cones, L-cones, and M-cones.

S-cones sense wavelengths of blue light, L-cones sense red light, and M-cones sense green light. When one or more of these cone types is affected, it hinders the cones’ ability to translate light to their designated color.

Inherited Color Vision Deficiency

Color blindness is usually a hereditary condition, meaning that you are born with it. Cases of inherited red-green color blindness are caused by a gene mutation in the X chromosome.

This makes biological males more likely to be born with red-green color blindness than biological females. Other types of achromatic vision are carried on different chromosomes, which means males and females are equally likely to inherit them.

Acquired Color Vision Deficiency

Those who are not born with achromatic vision may still experience color vision loss. Some of the underlying causes of acquired color blindness include:

- Eye conditions such as cataracts, macular degeneration, and glaucoma

- Injury to the eye or brain

- Neurological conditions that affect the brain, such as multiple sclerosis and Alzheimer’s

- Prescription medications such as sildenafil citrate, digoxin, ethambutol, hydroxychloroquine, and amiodarone

Unlike hereditary cases, acquired color blindness can worsen over time. See an eye doctor if you experience eye problems or start to notice a difference in your color vision. And be sure to discuss the potential side effects of new medications with your doctor before starting them.

How Common Is Color Blindness?

Different types of color deficiency have different levels of prevalence. Red-green deficiency, which is the most common type, affects approximately 1 in 12 males and 1 in 200 females.

Blue cone monochromacy also affects males more than females, but cases overall are much more rare — only 1 in every 100,000 people is affected worldwide. A bit more common, blue-yellow deficiency affects 1 in every 10,000 people, and males and females have an equal likelihood of having it.

Glasses and Contact Lenses for Color Blindness

Researchers have developed ways to bring the full-color spectrum to those with achromatic vision, and some companies have created indoor and outdoor lenses that help correct red-green color vision deficiencies.

The lenses work by filtering light wavelengths to increase the contrast between red and green. Doing so helps viewers better distinguish colors and experience a fuller visibility spectrum.

This idea has also been applied to contact lenses, but using a different method. Researchers infused gold nanoparticles into the contact lens material, which produced rose-tinted gels. The gels filtered specific light wavelengths to improve contrast where red and green overlap.

An added bonus to the gold-infused contact lenses is that they can be fitted with a vision prescription, unlike eyewear lenses that correct color vision deficiency.

While achromatic vision can’t be reversed, scientists are taking huge steps toward making temporary correction — and a world in full color— possible for the people who need it.